Memories, monuments, and Martin

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. led marchers from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery, Ala., to protest the denial of voting rights to blacks.

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. led marchers from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery, Ala., to protest the denial of voting rights to blacks.

While I didn’t grasp the profound power of symbols as a white kid growing up in the Charlottesville, I do now. And as an adult in today’s America, I feel the urgency to make sure our monuments stand for what’s best in our country. On MLK Day, join me in taking action for economic and social justice.

Minor Sinclair is the director of Oxfam America’s US Domestic Program

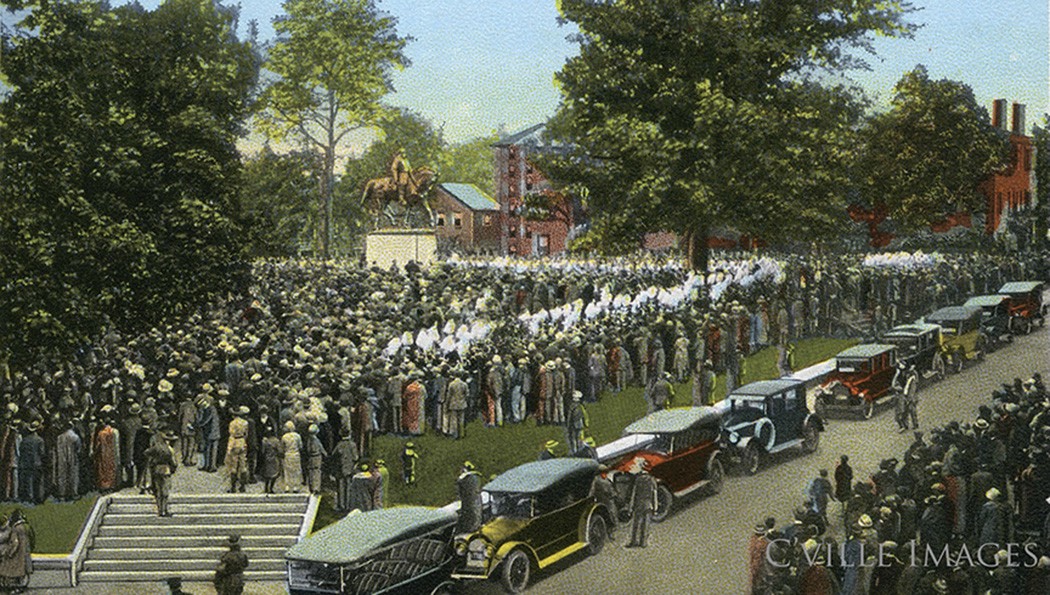

The statue of Robert E. Lee is still standing in Charlottesville, Virginia, five months after the white nationalist protests that killed one and injured 19. You can’t see it today, however: the Confederate general and his horse are shrouded in black plastic and tied down with ropes. What will become of the monument is uncertain; while the City Council voted to remove it, the Sons of Confederate Veterans filed a lawsuit to block that move.

So the fate of the statue hangs in the balance – and, in some respects, so does the future of race relations and reparations in our country.

Growing up in Charlottesville, I never paid much attention to the statue; I didn’t associate the idealization of Confederate soldiers with the continued racial oppression of the day. We never thought that Charlottesville local heritage would one day become a national symbol for racism in America. Over time, I’ve learned that Confederate imagery is not fundamentally about pride of place and “heritage not hate.” Simply put, Confederate monuments serve to inspire and propagate the ideals of white supremacy.

As a child, I was simply not aware of the subtle (and not-so-subtle) ways that Confederate symbols (monuments, flags, names of public places) were used as tools to elevate whites and suppress blacks. I never imagined the daily humiliation of African American students attending a school named after Jefferson Davis or Robert E. Lee (or (Col.) Venable, the elementary school I attended, named after an aide to Lee and, embarrassingly, a family forebear).

While the outcry to preserve (and proliferate) Confederate monuments in Charlottesville—and Memphis and New Orleans and elsewhere–may not represent majority opinion, the swelling of white resentment is powerful, and frightening. Indeed, white supremacists have shrewdly tapped into the political, economic, and cultural fears of the white working class and Southerners, which have been stoked by job loss, demographic change, and erosion of white privilege. This is nothing new: every time African Americans take a step forward, there’s a move to push them back. Each wave of emancipation, economic advancement, and voting rights is met with poll taxes, redlining, job discrimination, voter suppression.

Martin Luther King, Jr., perhaps more than any other resistance leader in the United States, understood the power of symbols to oppress — and, conversely, to liberate. When King led a voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965, he understood how to leverage imagery: blacks crossing the bridge to freedom, only to be violently beaten by a police force representing segregationists and Jim Crow policies.

“Shining moment”

“Selma, Alabama became a shining moment in the conscience of man,” King said to a crowd in Montgomery in 1965. “If the worst in American life lurked in its dark streets, the best of American instincts arose passionately from across the nation to overcome it. There never was a moment in American history more honorable and more inspiring than the pilgrimage of clergymen and laymen of every race and faith pouring into Selma to face danger at the side of its embattled Negros.”

Public symbols like monuments and school names should remind and inspire people of who we are as a society, what are our values and of what we are most proud. They should tell the truth. History should not be scrubbed or re-written to please the powerful. Instead, monuments like the Holocaust Memorial and the Vietnam Memorial remind us that the horrors of the past should never be repeated. Just one city, Montgomery, has 59 monuments and memorials to the Confederacy; it’s time to tear down the memorials to the oppressors and raise up the struggles of freedom and equality.

Bryan Stevenson and the Equal Justice Initiative are trying to do just that. They are building a museum and memorial on the site of a building that housed black slaves in Montgomery. They are memorializing the lives of the more than 4400 African American men, women, and children who were lynched by white mobs between 1877 and 1950.

Rather than glorifying soldiers and war, they are honoring the lives lost to racism and injustice. To remember the pain, to tell the truth of what happened, and to proclaim state-sanctioned racist violence should never happen again.

As King noted, “In Alabama little black boys and little black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today!” However, King did not just dream; he also challenged. These words are particularly poignant: “It’s not the violence of the few that scares me; it’s the silence of the many.”

Be vocal. Be active. Do justice.

On this MLK Day, a national day of service, I’ll be volunteering in Boston at the Pine Street Inn, which provides shelter to homeless men and women in the area. Find an opportunity near you.