Where Arms Flow Freely, Madness Follows: Staying Safe in Congo

Now I know what it’s like to get out of jail.

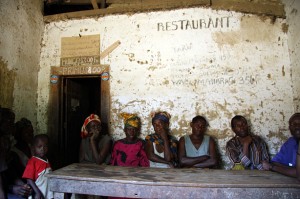

That’s the thought I had strolling down the main street in Beni a few weeks ago. It’s a town on the far eastern side of the Democratic Republic of Congo, in the heart of a region tangled for years in brutal conflict. After two weeks of traveling through the eastern provinces under strict security protocols that forbade wandering on foot and that required we be sequestered behind the thick compound walls of Oxfam guest houses or well-guarded hotels, this was something new: freedom.

Si, you can walk about. You can take yourselves to the market, said Luigi Viscardi, the exuberant Italian program manager in Beni. He himself heads out on regular 15-kilometer runs through the rutted streets. Did we want to come with him?

We felt giddy with liberation.

Beni was safer than other places we had been—Bunia, Goma, Bukavu. In Goma one day we drove by moments after a beat-up dump truck and a white UN truck had collided, leaving a smear of rubber on the road. Instantly, an angry-looking man, bristling with a gun, had appeared to take stock of the situation. It seemed to me an extreme reaction to an event that was probably all too common on narrow, crowded roads where traffic rules are hard to divine.

Beni was safer than other places we had been—Bunia, Goma, Bukavu. In Goma one day we drove by moments after a beat-up dump truck and a white UN truck had collided, leaving a smear of rubber on the road. Instantly, an angry-looking man, bristling with a gun, had appeared to take stock of the situation. It seemed to me an extreme reaction to an event that was probably all too common on narrow, crowded roads where traffic rules are hard to divine.

But in a place where arms flow freely, madness follows.

“They shoot,” said a colleague, describing the local police reaction to a student protest near his Goma house recently. “I heard a lot of fire yesterday. Normally what they use is Kalishnakovs.”

In Bunia, we learned from Marie Kanyobayo, the head of a women-based aid group, that guns streaming across the border from Uganda can be had for as little as $5—and that’s why she no longer rides her motorbike. It’s not safe: There are too many guns and too many people ready to use them in robberies.

We joked about KK Security, the private company that appeared to be doing a booming business in Goma. If any of us wanted to make a smart investment that would have been the business to go with. Its guards—and signs—were everywhere, including stationed at the entry to the Goma headquarters of MONUC, the largest UN peacekeeping force in the world.

But that joking masked a reality that was a strain to live with each day: Congo is dangerous. We felt it keenly every time we passed gun-toting soldiers (and there were plenty) knowing that they were underpaid and fended for themselves through extortion. We listened carefully to the stories about weak police forces and suspicious break-ins at aid compounds. And when night came, we were glad for those compound walls.

Beni was a break from all of that—a respite from the reality that so many people in Congo live with: fear.

Beyond Beni, we had plenty of measures in place to protect us. We had safe four-wheel-drive vehicles to ride in, and locked doors to sleep behind at night. We had radios and telephones to call for help—and the confidence that someone would respond. We had cash to pay for emergencies and insurance cards to bail us out.

Even as we sometimes chafed at it, that was the other half of our reality—the comfort of security. How many people in Congo have that?